DNA datasets are massive. A single human genome can use several gigabytes of storage in its most simplest form of storage. Certain forms of storage can even scale to 200 GB for a single genome alone. As DNA sequencing becomes cheaper, roughly 40 exabytes of genomic data are produced per year.

Efficiently storing and analyzing these sequences is a critical challenge. Furthermore, the ability to analyze large sequences of data are increasingly critical. In this post, we will explore a method to compress DNA using 4-bits per nucleotide in pure Rust, that allows us to generate Complementary base pairs in its compressed form.

This technique is especially useful in DNA analytical pipelines, where performance and memory constraints are critical. By minimizing the footprint of each sequence, we simultaneously reduce storage overhead and in-memory costs, without sacrificing speed or the ability to operate directly on compressed data.

Background

DNA Bases and IUPAC Codes

There are 15 IUPAC codes. The ones that most are familiar with are "A", "G", "C", and "T", representing the four standard DNA bases. However, DNA sequencing often produces ambiguous results. The remaining 11 codes are for these cases. For example, "R" can represent "G" or "A", while "N" can represent any nucleotide.

Click to show all 15 IUPAC codes

| Symbol | Bases | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | G | G |

| 2 | A | A |

| 3 | T | T |

| 4 | C | C |

| 5 | R | G or A |

| 6 | Y | T or C |

| 7 | M | A or C |

| 8 | K | G or T |

| 9 | S | G or C |

| 10 | W | A or T |

| 11 | H | A or C or T |

| 12 | B | G or T or C |

| 13 | V | G or C or A |

| 14 | D | G or A or T |

| 15 | N | G or A or T or C |

| source |

Complementary Base Pairs

DNA bases form pairs through well-defined chemical relationships: adenine (A) pairs with thymine (T), and cytosine (C) with guanine (G). These base-pairing rules extend to IUPAC ambiguity codes, which represent sets of possible nucleotides. For instance, "R" (A or G) complements "Y" (T or C).

There are three cases where the Complement is the same code. The bases "N" (any base), "S" (G or C), and "W" (A or T) all Complement to their own code (e.g. S->S, because "S" is represented by "G" or "C").

Design

Our compression system needs to be fast, small, and reversible. It should support all 15 IUPAC nucleotide codes and allow efficient I/O and transformation.

- Support for all 15 IUPAC codes.

- Smallest representation of nucleotides possible.

- Translate compressed/uncompressed DNA to and from file.

- Easily retrieve Complementary base pairs (including IUPAC codes)

Representing IUPAC Nucleotides in Four Bits

Since four bits are enough to represent 16 values (2⁴ = 16), we can comfortably fit in all 15 codes as well as an additional padding code.

Because Rust does not support native 4-bit types, our 4-bit encodings must be packed into a larger primitive. I opted to group 4 nucleotides into a single u16 integer. Because 4-bit data types are still represented at the byte level in Rust, we can squeeze four nucleotide representations of DNA into a single u16 integer.

When a sequence has fewer than four nucleotides remaining at the end, we use the 16th reserved value as a padding indicator. These padding values are ignored during decompression.

Support for Bitwise Rotation

To obtain support for 12 Complementations and 3 self-Complementations, we can rotate the bit two positions.

For example, "A" will be represented by 0001. Rotating two bits will give us 0100 "T". An additional two bit rotation will bring us back to "A", 0001.

Codes that Complement themselves must be symmetric on either half of the bit mask. For example, if we represent the code "S" ("G" or "C") as 0101, rotating two bits will still give us 0101.

Nucleotide Encoding

Let's first look at a simple match expression to see the final schema we have derived. This match expressions encodes each IUPAC nucleotide into a 4-bit mask:

let mask = match nuc {

'_' => 0b0000,

'A' => 0b0001,

'C' => 0b0010,

'T' => 0b0100,

'G' => 0b1000,

'R' => 0b0011,

'K' => 0b0110,

'Y' => 0b1100,

'M' => 0b1001,

'S' => 0b0101,

'W' => 0b1010,

'B' => 0b1110,

'D' => 0b1101,

'H' => 0b1011,

'V' => 0b0111,

'N' => 0b1111,

_ => {

panic!("Invalid nucleotide {}", nuc);

};This will serve as the building block for our 4-nucleotide compression scheme. Note that Complementary base pairs (e.g. G/C, or A/T) are rotated 2 positions!

Introducing NucWord

The NucWord struct represents four encoded nucleotides packed into a single u16. The methods from_str and to_string are used to serialize/deserialize.

pub struct NucWord(u16);

impl NucWord {

pub fn from_str(nucleotide: &str) -> Self {

// omitted for brevity...

}

pub fn to_string(&self) -> String {

// omitted for brevity...

}

}Encoding with from_str

Lets look closely at from_str:

pub fn from_str(nucleotides: &str) -> Self {

let mut out: u16 = 0;

for (i, nuc) in nucleotides.chars().enumerate() {

let mask: u16 = match nuc {

'_' => 0b0000,

'A' => 0b0001,

'C' => 0b0010,

'T' => 0b0100,

'G' => 0b1000,

'R' => 0b0011,

'K' => 0b0110,

'Y' => 0b1100,

'M' => 0b1001,

'S' => 0b0101,

'W' => 0b1010,

'B' => 0b1110,

'D' => 0b1101,

'H' => 0b1011,

'V' => 0b0111,

'N' => 0b1111,

_ => {

panic!("Invalid nucleotide {}", nuc);

}

};

out |= (mask as u16) << (i * 4);

}

Self(out)

}This simple method iterates through a slice of four nucleotides, translating each to its 4-bit encoding, and shifts them to their appropriate position in the u16.

Decoding with to_string

pub fn to_string(&self) -> String {

let mut out = String::new();

for i in 0..4 {

let bin = (self.0 >> (i * 4)) & 0b1111;

let nuc = match bin {

0b0000 => '_',

0b0001 => 'A',

0b0010 => 'C',

0b0100 => 'T',

0b1000 => 'G',

0b0011 => 'R',

0b0110 => 'K',

0b1100 => 'Y',

0b1001 => 'M',

0b0101 => 'S',

0b1010 => 'W',

0b1110 => 'B',

0b1101 => 'D',

0b1011 => 'H',

0b0111 => 'V',

0b1111 => 'N',

_ => {

panic!("Invalid nuc");

}

};

// Step to filter out padded nucleotides

if nuc == '_' {

continue;

}

out.push(nuc);

}

out

}This method takes a 4-bit mask to return a String implementation of our nucleotide, filtering out any padded characters.

NucBlockVec

Now that we can represent four nucleotides in a single NucWord, we will define a container type NucBlockVec to encode/decode entire DNA sequences.

pub struct NucBlockVec(Vec<NucWord>);

impl NucBlockVec {

pub fn from_str(nucleotides: String) -> Self {

let mut out = NucBlockVec(vec![]);

for i in 0..(nucleotides.len() / 4 as usize) {

let low = i * 4;

let high = (i * 4) + 4;

let str = &nucleotides[low..high];

out.0.push(NucWord::from_str(&str));

}

if nucleotides.len() % 4 != 0 {

let low = nucleotides.len() - (nucleotides.len() % 4) as usize;

let str = &nucleotides[low..nucleotides.len() as usize];

out.0.push(NucWord::from_str(&str));

}

out

}

pub fn to_string(&self) -> String {

let mut out = String::new();

for quad in self.0.iter() {

out.push_str(&quad.to_string());

}

out

}

pub fn to_bytes(&self) -> Vec<u8> {

self.0.iter()

.flat_map(|b| b.0.to_le_bytes())

.collect()

}

pub fn from_bytes(bytes: &[u8]) -> Self {

let mut out = NucBlockVec(vec![]);

let size = std::mem::size_of::<u16>();

for chunk in bytes.chunks(size) {

if chunk.len() == size {

let word = u16::from_le_bytes(chunk.try_into().unwrap());

out.0.push(NucWord(word));

}

}

out

}

}Our First Test

Let’s define a quick test to see the compression in action. We will read our input.txt, encode the nucleotides to NucBlockVec, and write the compressed binary output to disk.

The input.txt file contains the complete human mitochondrion genome, which is sized at 16,569 bytes.

use std::{fs::File, io::{Read, Write}};

use std::io::BufReader;

fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

let mut dna = String::new();

BufReader::new(File::open("input.txt")?).read_to_string(&mut dna)?;

let dnablocks = NucBlockVec::from_str(dna);

let compressed = dnablocks.to_bytes();

File::create("output.txt")?.write_all(&compressed)?;

Ok(())

}Inspecting output.txt file size, we have 8,286 bytes... Exactly half the size!

Generating Complementary Base Pairs

Here’s how we implement base-pair complements using our bit rotation trick:

impl NucWord {

// ...

pub fn Complement(&mut self, i: usize) {

let shift = i * 4;

let mask = 0b1111 << shift;

let to_mask = (self.0 & mask) >> shift;

let complement = (to_mask << 2 | to_mask >> 2) & 0b1111;

self.0 = (self.0 & !mask) | (complement << shift);

}

pub fn Complement_each(&mut self) {

for i in 0..4 {

self.Complement(i);

}

}

}This works because the 4-bit encodings were designed so that a 2-bit rotation produces the nucleotide's complement.

Lets compare this bit rotation to a simpler match implementation:

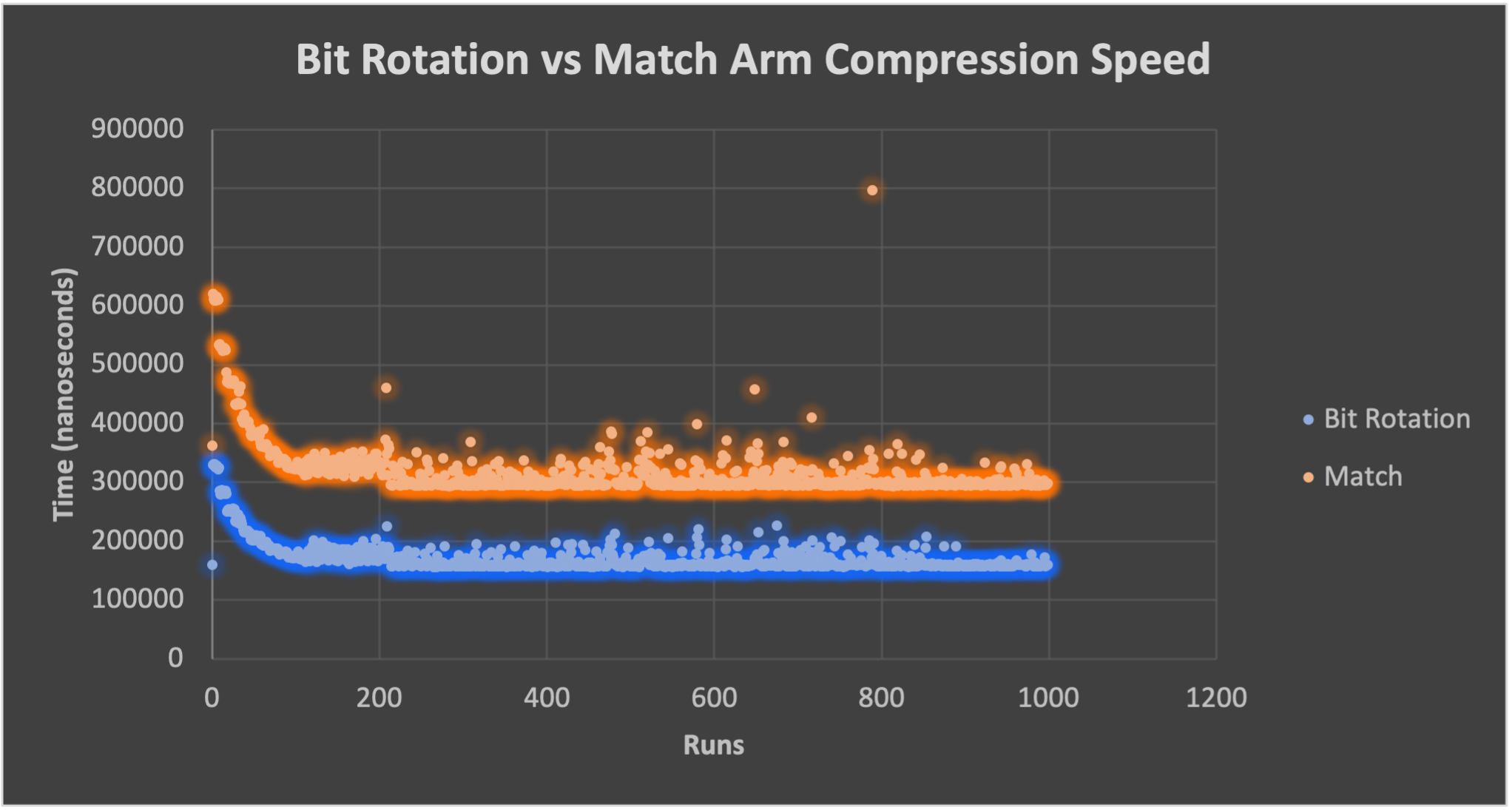

Bit rotation vs match arm for DNA Complement

Bit rotation vs match arm for DNA Complement

Bit rotation is roughly 2x faster (Fig. 1) than using a match arm to grab DNA base pair Complements.

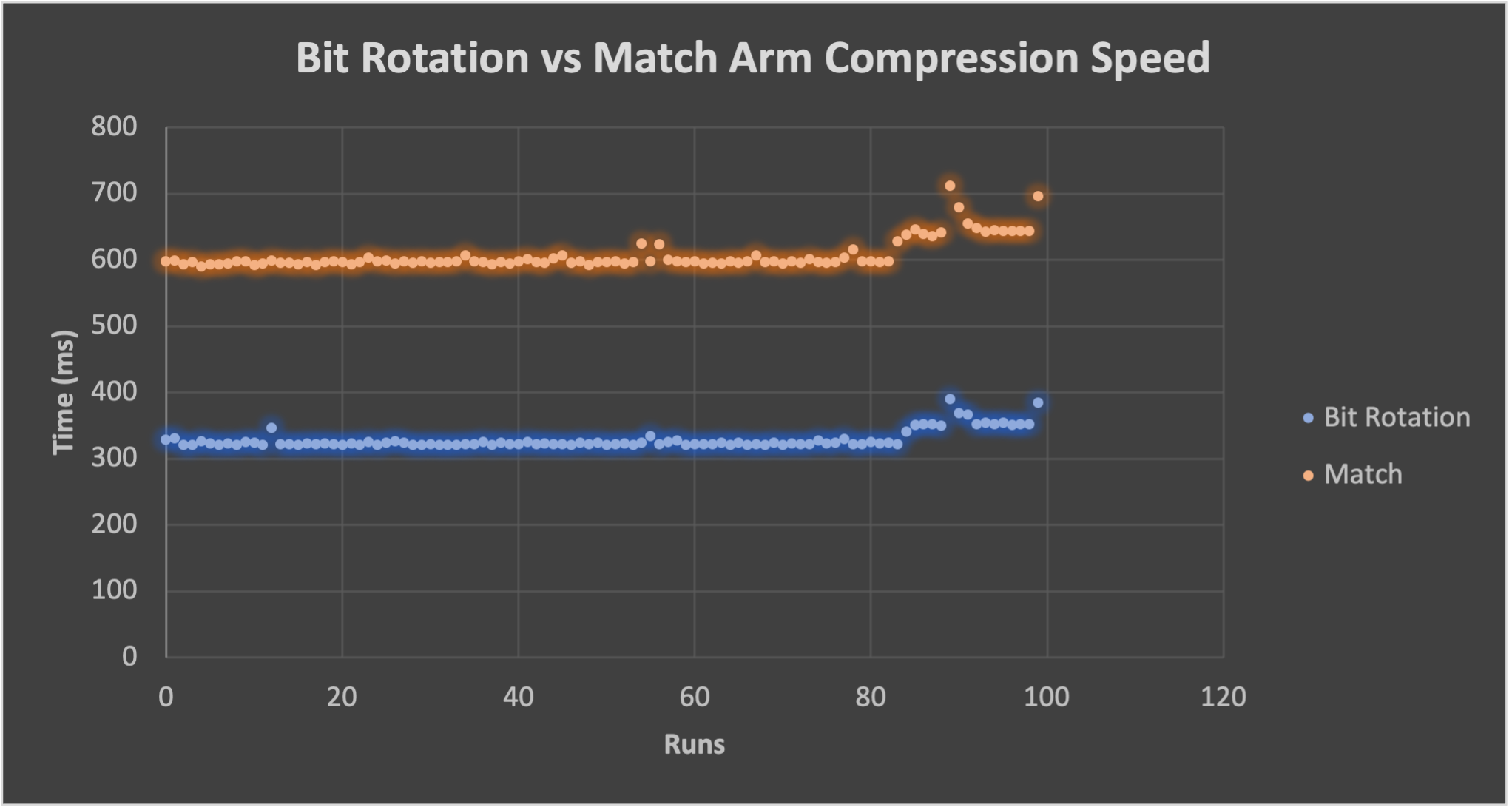

The speed savings becomes more important when dealing with very large nucleotide sequences. In Fig. 2, the time is reduced from ~0.6 seconds to ~0.3 seconds.

Bit rotation vs match arm for DNA Complement for large Drosophila Melanogaster nucleotide sequence

Bit rotation vs match arm for DNA Complement for large Drosophila Melanogaster nucleotide sequence

Conclusion

Efficient DNA compression is a challenging problem at the intersection of systems programming and bioinformatics. This Rust based 4-bit DNA encoder offers a lightweight, fast, and ergonomic way to handle genetic data efficiently.

Using bitwise operations doubled Complementary generation speed. I feel I've only scratched the surface and look forward to getting more use out of this encoding.

Check out the source code on my GitHub. Thanks for reading!